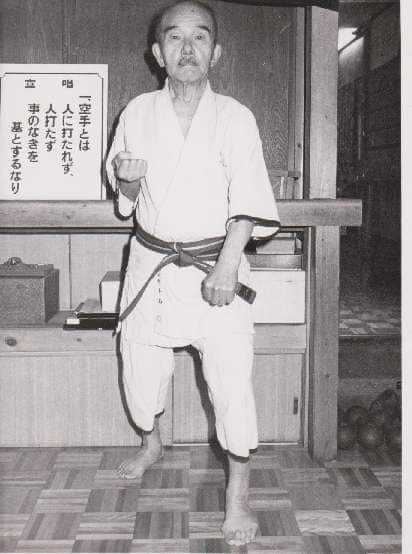

Almost forgotten Yasuhiro Konishi sensei

By pure chance (though I don’t really believe in chance), I came across an old Japanese karate book from 1956 that had been digitized and archived at the National Museum of Hawaii. The author is Konishi Yasuhiro sensei. What caught my attention was how he connects karate with kendō—since Konishi wasn’t just a karateka but also a skilled kendōka.

I decided to use modern technology to extract and translate the original Japanese text. I was deeply curious to discover what Konishi sensei had to say and what experiences shaped his path. I’d like to share some of Konishi sensei’s insights, as I find myself closely aligned with many of his ideas.

Who Was Konishi Yasuhiro?

Konishi Yasuhiro (小西康裕, 1893–1983) was a prominent Japanese budōka and founder of Shindō Jinen-ryū Karate-jutsu. He played a key role in spreading Okinawan karate throughout mainland Japan before and after World War II. He is especially known for his efforts to integrate karate with the principles of traditional Japanese budō—particularly kendō and aikidō—creating a system that aimed for both physical mastery and spiritual development.

Konishi began his martial arts training with jujutsu at the age of six. Seven years later, he started kendo and later attended Keio University, where he also coached the university’s kendo club.

A fellow kendoka at Keio, Tsuneshige Arakaki from Okinawa, once demonstrated a karate kata at a party, which immediately intrigued Konishi. He started learning karate from Arakaki, and after graduation, briefly worked for a company. In 1923, he opened his own dojo—the Ryobu-kan—where he taught kendo and judo and continued deepening his understanding of karate.

The Rise of Karate in Japan

The early 1920s were a formative time for karate in Japan. In 1922, Gichin Funakoshi gave a public karate demonstration at the Kodokan, judo’s headquarters, gaining widespread attention. In 1924, Funakoshi approached Konishi about renting space at the Ryobu-kan. At the same time, other Okinawan masters, Choki Motobu and Kenwa Mabuni, also used the dojo for their own training.

Meanwhile, Konishi continued his kendo studies under Nakayama Hakudo, one of the most revered sword masters of the time. He also trained with Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of aikidō, who encouraged him to create a new karate kata based on a formal system of footwork.

The Deeper Meaning of Karate

In our modern age—where culture thrives and civilization expands—we need to reconsider what "karate" truly means. Too often, it’s viewed merely as a system of self-defense, a fighting style, or a sport focused on defeating opponents. But this perspective is superficial and overlooks the deeper essence of the art.

Originally, karate wasn’t about defeating others or launching attacks. Its true purpose lies in harmonizing body and mind, in disciplining the spirit, and in achieving unity with nature and the universe. It shares the philosophy that "heaven, earth, human beings, and all things are one."

Karate, in this light, is a discipline of balance—a spiritual and physical practice meant to bring harmony into daily life. It's not just a physical exercise, but a spiritual path, a way to achieve inner peace, clarity of mind, and moral strength. In that sense, karate could be called a kind of “philosophical movement practice”—a physical expression of inner life.

When we think this way, we see that all true forms of art—painting, music, the tea ceremony, or flower arranging—are expressions of the same spiritual harmony. Karate, too, reflects the deep human longing to be one with nature and with oneself.

The word “kara” (empty) doesn’t mean “nothingness,” but rather openness, spaciousness, and detachment. This “emptiness” is the essence of spiritual freedom.

So when we speak of karate, we’re referring to a way of training that integrates physical technique with mental clarity—a way to live fully, freely, and purposefully.

Four Approaches to Karate

Karate has long been viewed through four major lenses:

- As combat – a system of fighting and self-defense aimed at defeating an opponent.

- As physical education – a method of improving health and fitness.

- As spiritual training – a discipline to develop character, moral strength, and inner growth.

- As sport – a competitive activity governed by rules, emphasizing performance, discipline, and measurable achievement. (Radek Januš: I’ve added this fourth element, as it reflects an important and valid perspective in today’s world as well.)

While these approaches are often taught separately, they are deeply interconnected. Real karate includes all dimensions.

From ancient Chinese philosophy comes the concept of taikyoku (the Great Principle), sometimes translated as the "grand unity"—a balance of body, mind, and spirit. Physical skill alone is not enough; even technique is meaningless without a spiritual foundation.

That’s why we say: “Karate begins and ends with respect.” Not just a bow, but a profound attitude of reverence—for oneself, for others, and for all of life.

Karate-jutsu: The Art Behind the Technique

Today, the term “karate-jutsu” is more widely known. But even among those who claim to practice karate, few truly grasp its deeper meaning.

Karate-jutsu is not just a fighting method. It is a way of refining the body and mind, a path toward self-mastery. In pre-war Japan, karate practitioners were often misunderstood—viewed as eccentric or even violent—partly because the public lacked understanding, and partly because many karateka couldn’t express the deeper essence of the art.

Today, with growing interest in physical and moral education, karate is increasingly seen as a path of holistic development.

True karateka must not only learn the techniques but understand karate as a dō (道)—a way of life. One that serves society, builds relationships, and leads to fulfillment.

“Kara” (空) refers to inner clarity and openness, not just “empty hands.” It points to an ideal: being free of ego, pride, and attachment.

“Te” (手) means “hand”—the expressive, physical aspect.

Together, they form karate: “the empty hand”—ready, open, and present.

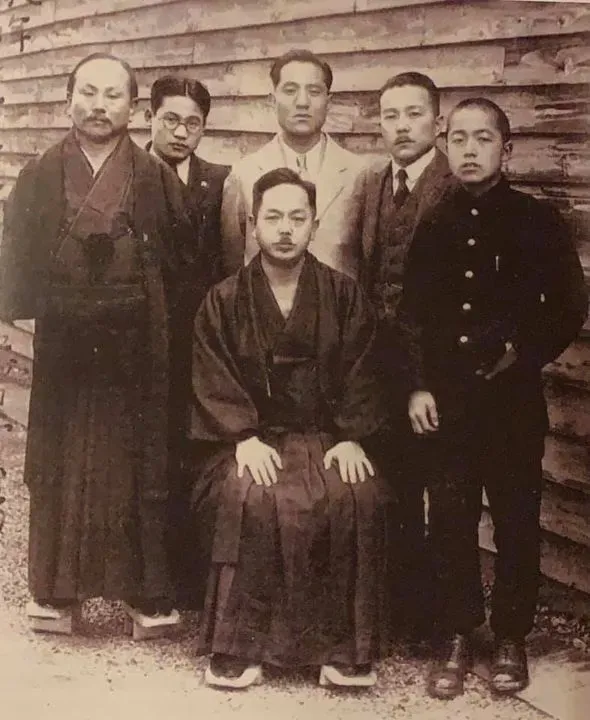

Konishi Yasuhiro sense with Mabuni Kenwa sensei and Motobu Choki sensei

The Active Nature of Karate

Karate is not passive defense—it is an active engagement with life. An old proverb says, “Use what you have.” Karate embodies this principle—whether it's space, time, body, or breath, everything becomes part of the strategy.

A key term is katsuyō (活用)—“creative use.” In ancient martial arts, this meant moving like water, adapting like air. Karate applies this principle not only in technique but also in attitude and spirit.

True karate is not about brute force. It's about sensitivity, awareness, and timing. It's about reading the situation and turning threats into opportunities.

Karate is an art of receptivity (uke)—not passive, but transformative. It turns the energy of an attack into a source of advantage. It is not about defeating others, but about mastering oneself and the moment.

“One Movement, One Hundred Applications”

A traditional saying goes:

“If you master one thing, it can be applied in a hundred ways.”

For example:

- The same hip rotation applies to strikes, throws, and movement.

- Breathing techniques apply equally in kata and self-defense.

You don’t need to learn hundreds of techniques—you need to deeply understand one. That’s the essence of true training.

Kata: The Living Forms of Karate

“Karate no kata wa ikite iru” – Kata are alive.

Kata are not empty rituals. They are concentrated wisdom passed down through generations. If practiced without intention, they become hollow. But with breath, spirit, and rhythm, they come alive.

Konishi emphasized:

- Kata are not just physical forms—they train the mind and spirit.

- Each kata contains principles of attack, defense, breathing, and energy flow.

- As the practitioner grows, so does the kata—it evolves.

Kata is a living method, not just a pattern.

Karate Begins and Ends with Respect

The famous saying:

“Karate begins with rei and ends with rei” (礼に始まり礼に終わる)

expresses the soul of karate.

Rei is more than a bow. It is:

- Respect for the teacher.

- Awareness of your partner.

- Presence of mind.

- Courage and humility.

Without respect, there is no karate—no matter how skilled the technique.

Karate and Kendō (Kenjutsu)

Kendō—Japanese fencing—has long been practiced in Japan not only as a method of combat, but also as a means of spiritual cultivation. An experienced kendō practitioner learns to sense an opponent’s intention before it even manifests through movement. From this perspective, there are many shared elements between kendō and karate.

A core principle in kendō is that “a strike is delivered at the moment the opponent exposes a gap”—whether in mind or body. This same idea appears in karate, where techniques should be applied precisely when the opponent loses balance, focus, or defensive structure. In this sense, kendō is an ideal training ground for developing perception and timing.

Japanese swordsmanship—especially its modern form as kendō—is often criticized for being too formal or impractical. But if we look into its history, we find many kenjutsu schools that dealt with real combat. They developed methods to strike in harmony with breath, posture, and intention.

The lesson here is clear: karate, too, should be studied with similar depth—not just learning how to strike, but also when to strike, why to strike, and in what state of mind. Ultimately, kendō is a school of mental discipline, and this aspect deserves to be more fully integrated into karate as well.

Karate and Aiki Budō

Konishi reflects on the connection between karate and other martial arts—especially aiki budō. The techniques of Ueshiba Morihei, founder of aikidō, reveal harmony rather than force. Victory comes through blending with an opponent’s energy, not overpowering them.

This is true mastery: the ability to be soft yet effective. Aiki budō teaches that the highest level of martial arts is spiritual unity, not domination.

Karate as a Healing Art (Ishinjutsu)

Konishi also discusses the role of kiai—not just as a fighting tool, but as a form of healing. Through breath, posture, and focused energy, karate becomes a tool for balancing body and mind.

He shares stories of people who regained their health through disciplined training. Karate, practiced correctly, strengthens both vitality and inner harmony.

This is Ishinjutsu—the art of healing the body. Not a replacement for medicine, but a complementary path of awareness, breath, and balance.

Karate and Health

In a modern world where people grow physically weaker and mentally overstimulated, karate offers a return to natural strength and calmness.

Konishi observed that his students who trained earnestly got sick less often and faced life’s challenges with greater resilience.

Practiced properly, karate strengthens organs, breath, and circulation, and aligns body and mind. Movements in karate are not random—they are designed to balance energy and muscle use across the body.

Konishi cites even Western doctors who support karate as a form of rehabilitation and mental hygiene. Karate, he says, is a preventive system, ideal for people of all ages.

If not treated as a sport or a pursuit of victory, but as a path of inner refinement, karate can be a way to live well—into old age.

In closing, I believe that karate today holds deep relevance—not just as a martial art, but as a path toward a balanced, vibrant, and meaningful life. By connecting it with other martial arts—especially kendō—in a spirit of symbiosis, we can deepen the skills and understanding of every budōka.